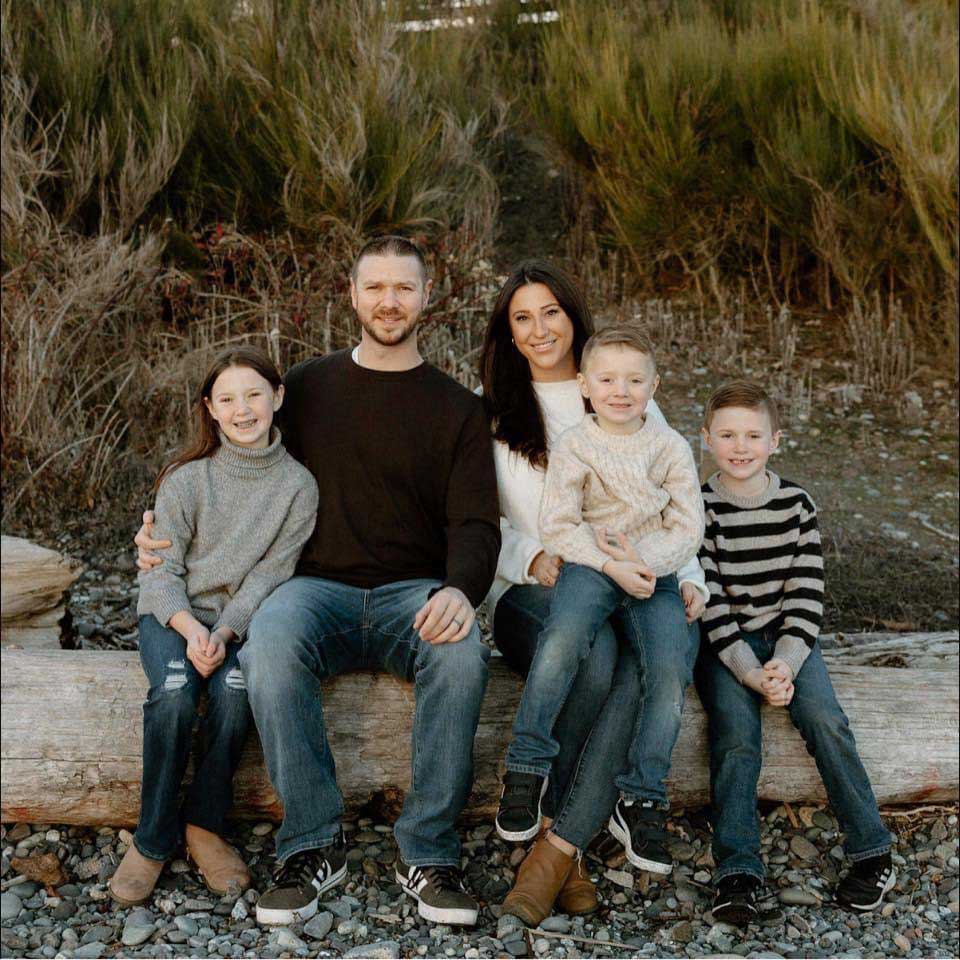

Beckett’s Journey: Overcoming the Challenges of Rare Disease Diagnosis With Help From ARUP Autoimmune Disease Testing

Beckett’s Diagnostic Odyssey

On June 13, 2024, Whitney Lippincott walked into the emergency department of Intermountain Primary Children’s Hospital in Salt Lake City and refused to leave until her 6-year-old son, Beckett, was admitted. In just two weeks, Beckett had transformed from an active, healthy boy who loved sports into one who struggled with basic daily tasks, such as climbing stairs, lifting silverware, and getting out of the bathtub.

During those two weeks, the Lippincotts rotated in and out of urgent care facilities and emergency departments in their search for answers. Each time, they were told that Beckett’s symptoms were likely caused by a viral infection.

“They were telling me to go home and wait, but I had this motherly intuition that something was really wrong,” Whitney said.

After he was admitted to Primary Children’s, Beckett spent another week enduring test after test, including a difficult bone marrow biopsy to investigate whether he had leukemia.

Beckett weathered the procedure with astonishing fortitude, with the help of a trusted companion—his blanket. “The nurses were so kind to let Blanky go through the procedure with him,” Whitney said.

“When an illness happens, you believe that doctors are superhuman and they will be able to figure it out right away,” Whitney said. “We kept hearing, over and over again, ‘This is weird. This is odd. His blood looks odd.’”

For patients who are suffering from rare diseases, as Beckett turned out to be, the journey to diagnosis can be onerous, stress inducing, and filled with unknowns. Arriving at the right diagnosis is challenging and, in Beckett’s case, required a joint effort from persistent family members and knowledgeable physicians, as well as access to reliable and fast lab testing.

“It’s like finding the right needle in a stack of needles,” Whitney said.

Rare Disease Diagnosis: Juvenile Dermatomyositis

In the above video, Beckett, Zack, and Whitney Lippincott discuss the onset of Beckett’s illness, its eventual diagnosis, and what followed.

Eventually, Beckett’s case reached Karen James, MD, MSCE, a pediatric rheumatologist at Primary Children’s and an instructor at the University of Utah Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine.

“This case was particularly hard because it looked like a bad viral illness in the beginning. Our initial recommendation was to wait and see what happens. During that time, repeat labs showed worsening muscle inflammation and cytopenia [abnormally low levels of red or white blood cells or platelets],” James said. “He had this atypical presentation, and we weren’t entirely sure what was happening.”

As Beckett’s symptoms worsened, James began to suspect an autoimmune disease. She ordered laboratory testing, which was performed at ARUP Laboratories, to measure the concentration of certain enzymes that can leak from muscles when they are inflamed or injured, including creatine kinase (CK), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL).

According to James, elevated enzyme levels detected by just two of these tests would be sufficient for an autoimmune diagnosis, but Beckett’s lab results showed that all five were elevated.

James also ordered testing to detect antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), which are strongly associated with connective tissue diseases, and von Willebrand factor, a marker associated with endothelial cell activation. Beckett’s ANA test was positive. The von Willebrand factor result was initially in the normal range but increased to abnormal as his disease progressed.

“It’s so important that we get those results back quickly to begin treatment,” James said. “When I started working [at Primary Children’s], I was thrilled to learn about ARUP. It’s so nice to have a national reference lab right down the street where we can get reliable lab results.”

After receiving results, James diagnosed Beckett with juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM), a rare autoimmune condition that is characterized by skin rash and muscle inflammation. According to James, the most likely cause for the condition was a mononucleosis infection that occurred simultaneously with extensive sun exposure.

The Lippincotts had visited a splash pad on June 1 and noticed an unusual redness in Beckett’s face shortly after.

JDM is a rare disease that affects only one in 1 million children. If left untreated, JDM can result in permanent muscle atrophy, as well as damage to the lungs and gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

“We were so lucky with how quickly we were able to get lab results back and how quickly they were able to diagnose [Beckett],” Whitney said. “We started treatment right away, which saved him from long-term damage to his muscles.”

The Vital Role of Laboratory Testing

Testing for autoantibodies provides important insights for clinicians, in addition to confirming diagnosis. Myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibodies can be helpful in determining treatment course and in predicting the disease course, James explained.

Antibodies play an important role in our immune systems because they identify and attack foreign cells, such as viruses. Autoantibodies are malfunctioning antibodies that mistakenly attack the body’s own cells.

“The myositis-specific and, to some extent, myositis-associated antibodies give us some prognostic information,” James said. “Certain antibodies are associated with the more chronic disease course, some are associated with having more skin disease, and some are associated with having more internal organ involvement, such as interstitial lung disease or GI ulcerations.”

Lisa Peterson, PhD, D(ABMLI), is a medical director of Immunology at ARUP who oversees ARUP’s myositis panel testing and is guiding the development of assays to detect additional antibodies associated with myositis.

She said there are multiple methods to detect the relevant autoantibodies, some of which are more accurate than others. One method, immunoblot, is relatively easy and involves using strips of membrane coated with target antigens to detect the presence of myositis-specific antibodies.

However, the gold standard method for detecting myositis-specific autoantibodies, immunoprecipitation, is more time consuming and more labor intensive. This method involves radioactively labeling proteins and allowing them to bind to antibodies in the sample, using an electric charge to separate bound proteins by their molecular weight across an electrophoresis gel, which then has to be incubated with a piece of film to amplify the radioactive signal until it can be developed and interpreted. The resulting bands are then compared with known molecular weights to identify which proteins are present.

ARUP is one of only three labs in the country that offer a myositis panel by immunoprecipitation.

“There are numerous publications on issues with false positives and false negatives using the blots alone,” Peterson said. “We try to take more of an integrated approach. We use the results from immunoblot in combination with the results from immunoprecipitation and other methods to interpret testing. It really requires an integration of multiple methods to provide accurate results.”

According to Peterson, autoantibodies can give important indications about the progression of disease or the development of new symptoms. For example, melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) antibodies can be associated with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. ARUP calls to alert clinicians when results of MDA5 tests are positive.

Other antibodies are associated with cancer, although that is more common in adults with dermatomyositis than it is in children.

“We depend on ARUP for our ANA testing and the autoantibodies [testing] because we find their results to be reliable and interpretable,” James said.

Beckett’s results for the myositis panel were negative, which is “likely reflective of the fact that we don’t yet know all of the autoantibodies that are out there for myositis,” James said. She wasn’t surprised by the negative result, due to the atypical pattern of Beckett’s disease symptoms.

Research in this field is ongoing, and ARUP regularly evaluates new antibodies for the panel. In early 2025, ARUP will add Ha, Ks, and Zo autoantibodies to its panel.

“The good news is that we have treatments. The bad news is that I can’t predict the future for [Beckett],” James said. “Some kids will have this once. Other kids will have a more chronic course, and the disease is harder to get under control.”

Beckett’s Road to Recovery

Beckett was discharged from Primary Children’s on June 21 to begin his long road to recovery. His routine now involves daily doses of medications, including an initial high dose of steroids, and he faces a two-year course of chemotherapy and, for a time, weekly intravenous infusions of antibodies.

“All that matters is that he’s healthy and on the mend,” Whitney said. “At the same time, we’re mourning the loss of who he was two months ago and saying goodbye to that kid for a little while, until he is back to where he needs to be.”

According to his mom, Beckett has become an expert at swallowing pills and taking shots. Beckett says the “needle feels like a cotton swab.”

With treatment, Beckett is slowly regaining strength in his muscles. He was able to return to school, albeit with a few modifications. He now needs to apply sunscreen before recess to limit the effects of sun exposure. Depending on his symptoms, he may need grading exceptions because of his muscle weakness, which affects skills such as handwriting.

When asked what he was most concerned about, Beckett said, “That my friends won’t recognize me.”

Some of the medications have unfortunate drawbacks. The steroids have left him with a puffy face and weight gain.

Beckett looks forward to playing baseball and lacrosse again when his strength returns.

“Beckett has been our little superhero. He is so brave. I can honestly say that. I don’t think I’ve seen one tear throughout this entire process,” Whitney said. “He really tapped into this inner strength and understood that he needs to be strong.”

The Lippincotts plan to host a fundraising walk next summer to raise awareness of JDM. Proceeds from the event will go to the Cure JM Foundation.